In Part 4: Finding Words, we chose the subject matter for our poem, and we began to refine it by removing unnecessary words. But how do we know which words to discard and which words to keep? All the way back in A Problem To Solve, when were struggling to describe feelings with language, we decided that using words like “very”, “extremely”, or “thoroughly” to make something sound more intense didn’t do a terribly good job. However, even though we have chosen to describe meaningful events that can make Earnest experience intense feelings for himself, we still need to use intense language in our descriptions. How do we know what kind of words to use? How do we know when to use little words and when to use big words?

Imagine we see a big dog. A very big dog. Naturally, we want to share this curious event with our serious young friend Earnest:

I have seen a very big dog.

Earnest will think of large dogs he has seen in the past. Perhaps he will think of a Rottweiler or a Doberman.

No, no, Earnest! A very big dog. An extremely big dog!

Now, Earnest might think of the biggest dog he has ever seen, or perhaps even a dog a little bigger than that. But, being so very serious and sensible, it won’t be much bigger. As you recall, the dog we saw was so tremendously big that we could have ridden around on its back like a cowboy on a bronco. Poor Earnest will have no idea. This won’t do at all!

The problem with words like “extremely” is that they are used so commonly, they lose their true meaning. “Extremely” should really mean “close to the extreme”, or in other words, “as much, or almost as much, of a certain thing as it’s possible to be.” An “extremely big dog” should be a dog that’s as big as a dog can be (which, as we have seen, is very large indeed!)

However, because Earnest hears “extremely” rather a lot, when we say the word he doesn’t think about what its definition in the dictionary is. His mind jumps straight to the everyday meaning of the word. For Earnest, the everyday meaning of the word is taken from the time Charles said it was “extremely unfair” that his mother wouldn’t let him have a second serving of cake, or when Michael thought it was “extremely unlikely” to rain on Tuesday. But in fact, it was only a little unfair for Charles’ mother to stop him from eating so much cake (for it would not do to have an upset stomach), and it was only fairly unlikely for it to rain on Tuesday (for it does rain at this time of year). Every time Earnest hears “extremely” used to mean something that isn’t extreme at all, its true meaning becomes worn away a little more. Now that we need to tell him about something that really is close to the extremes of what is possible, “extremely” simply isn’t intense enough.

Choosing which word to use to describe something is like choosing which tool to use when making dinner. Everyday language is like a cook’s knife; it is fairly good at many different tasks. It’s important to know how to use it properly because we use it to prepare almost every meal. In fact, it’s often the only tool we need. But because we use it so much, it doesn’t keep a razor-sharp edge, and it can be hard to use for some delicate tasks.

The word “extremely” is like a boning knife; it should be very good at one particular thing and hopeless at everything else. It’s possible to use a cook’s knife to bone a fish, but only the most deft and practiced cook can do so well. For most of us, the boning knife is the better tool because every part of its shape and structure has been designed with removing bones in mind.

The problem is that Charles has been using our boning knife to chop tomatoes, and Michael has been using it to open cans, tasks that it was not designed to do; it’s now bent and blunt and not much use to anyone. If we try to use it to bone our fish now, we’ll be hacking away for hours and we still won’t be able to remove the bones well.

We need to reach to the very back of the drawer and find a knife that hasn’t been used for anything else, a knife that is still sharp and well suited to our particular task.

So, perhaps we can use a word Earnest doesn’t hear very often. What if we say to Earnest:

I have seen a Brobdingnagian dog.

Earnest, despite being sensible to a fault, has never heard the word “Brobdingnagian” before. Never one to shy away from a challenge, he will search out the very largest dictionary he can find and see that the word “Brobdingnagian” refers to an inhabitant of Brobdingnag, a made-up country in a book called Gulliver’s Travels by a man named Jonathan Swift. And because he is so very serious, Earnest will borrow his father’s copy of Gulliver’s Travels and pore through it until he finds the section that describes the land of Brobdingnag. He’ll read that the Brobdingnagians are sixty feet high with a stride that spans ten yards. When we next see Earnest, he’ll say, “That dog must truly have been the biggest that has ever come to the village!”

Because “Brobdingnagian” is not a word Earnest hears often, it has only a very particular meaning for him: something very large indeed.

And that is all very well, but it was rather a lot of work for poor Earnest, and many people are not nearly so patient or curious as to look up the meaning of a word as intimidating as “Brobdingnagian”. In choosing a word to use, we need to balance ease-of-understanding with intensity-of-meaning.

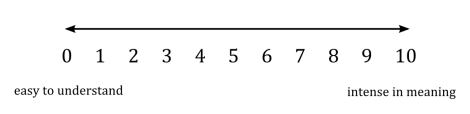

What if we plotted this relationship on a line? It might look something like this.

On this scale, the word “big” would be a zero or a one, and the word “Brobdingnagian” would be a nine or a ten. “Extremely big” might be a three, “tremendous” and “enormous” might be a four or a five, and “gigantic” might be a six. More unusual words like “behemothic“, “elephantine” or “cyclopean” would be closer to the top of the scale. We can see that as words become less commonly used, their meaning becomes more intense. We can use this scale to find balance between using easy words and difficult words; we don’t want to confuse people with complicated language when it isn’t necessary.

This scale works fairly well for describing a very large dog; we could even use the same scale for words that mean “very small” or “very hot”, or any other type of meaning that relies on intensity.

But what if we see a particularly unusual color of butterfly and want to describe its color?

We can call the color “red”, but “red” is a very general word. The butterfly’s color isn’t any more intense than “red”; it just isn’t quite the same everyday red of tomatoes or strawberries. If we think of less common words for “red”, we might light upon “scarlet”, which matches the butterfly a little better. If we think for longer we might eventually reach “terracotta“, the color of baked clay, which is closer to the color of the butterfly even than “scarlet”. And if we think for a very long time indeed and consult many long books full of difficult words, we might at long last settle upon “vermilion“, which is a very fine word indeed to describe the color of the butterfly, for it is vermilion through and through.

But the butterfly is also red. Vermilion is simply a type of terracotta, and terracotta is simply a type of scarlet, and scarlet is simply a type of red. Any of those words could correctly describe the color of the butterfly; vermilion is just the most precise word.

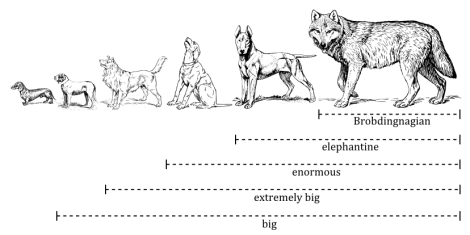

In fact, if we think back to the words we used to describe the dog, “Brobdingnagian” is nothing more than a type of “elephantine”, which is, in turn, simply a variety of “enormous”, which is a subset of “extremely big”, which is itself a type of “big”.

If we were to draw the relationship between these words, it might look something like this:

We can see that “Brobdingnagian” is a useful word not only because it is very intense, but because it is very precise. “Big” could mean a great range of sizes (from the second-smallest dog to the largest); “enormous” could mean a reasonable range (any of the three largest dogs); but “Brobdingnagian” could mean only a very narrow range (the largest dog). It is a useful word because it hones in exactly on what we want to say.

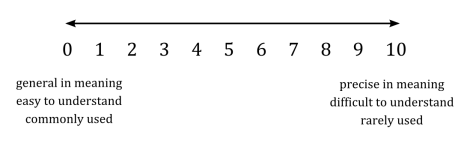

We can use this to update our original line:

But hang on! What if that butterfly hadn’t been vermilion but had been black? “Black” is a very commonly used word, but it has a precise meaning. Unlike red, there aren’t many shades of black. So where would that word fit on our scale?

And what if we had thought of the word “rufescent” instead of “vermilion”? “Rufescent” is a very rarely used word for red, but it doesn’t mean a precise color like “terracotta” or “vermilion”. So where would that word fit on our scale?

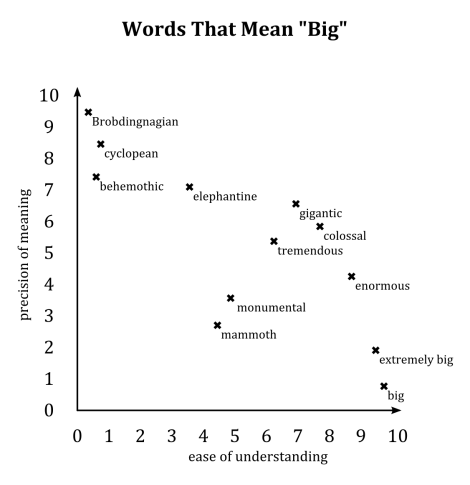

“Rarely used” and “precise in meaning” usually go together; “commonly used” and “general in meaning” usually go together. But there are many exceptions. We know that it’s better to use easy-to-understand words when possible, because what we say we will be less confusing, and it’s better to use precise-in-meaning words when possible, because they will express what we want to say more finely. We can plot precision of meaning against frequency of use to see how useful a particular word is.

The best words possible will score well on both axes and be at the top-right of the graph. However, as we’ve discovered, being frequently used tends to wear down a word’s meaning, so there aren’t any that score a ten on both scales.

The worst words will score close to zero on both axes. They are both hard to understand and vague in meaning. They confuse people with their unfamiliarity and yet, even when encountered by someone who happens to know what they mean (someone even more serious and sensible than Earnest–imagine!), they fail to be specific and precise. These are the words to avoid at all costs.

We can see from the graph that, for describing the very large dog, “gigantic” is a better word than “tremendous” because it is both easier to understand and more precise in meaning. In the same way, “cyclopean” is a better word than “behemothic” (perhaps because more people know of the cyclops than the behemoth). Of course, if Earnest happened to have a keen interest in the Book of Job and no interest at all in Greek mythology, than the rating for those particular words might be different (but, as we know, Earnest loves nothing more than reading Hesiod and Homer).

Which words we choose to use depends on how precise we need to be. When we tell Earnest about the very big dog, it’s important for him to understand just how large a dog it is (for otherwise, it is a very boring story). It makes sense to use a precise word like “brobdingnagian” or “cyclopean”, even if it might seem a little confusing at first.

If we wanted to tell Earnest that the dog had bitten us, the word “enormous” or “extremely big” would do perfectly well, for all we would want Earnest to understand is that he needed to fetch the doctor.

One thing we must never do is use a word that is difficult to understand just to make ourselves feel clever. It won’t do for all of our words to be long and difficult to understand, just as it wouldn’t do to have one knife for chopping tomatoes and another for dicing onions and another for slicing carrots and yet another for mincing garlic. Our kitchen would become hopelessly cluttered and we would trip over ourselves at every turn.

The secret to fine writing is to find the right balance between making your readers think about the words you have chosen and making your writing easy to understand. Hopefully, the tools we have developed together will let us choose the right words for our poem.

In the next post in the series, we will see if the same tools and balance can be applied to other aspects of our poem.

Please keep these up. At least I am still reading them.

Agreed!

Part 6 should be up in the next few days. Happy holidays everyone!

This has been one of the most engrossing and interesting things I have read in a long time…this could easily become a textbook on poetry if you went far enough with it! Keep up the good work.

Is there going to be more in this series? I’ve been finding it very enlightening.

i found this website by way of reddit , when is your next post going to be up? this is a fantastic series! and as a physicist, i am beginning to learn something of the foundations of poetry, of which i have never had that much of an ability to grasp previously

Please keep these coming. I’m hopelessly hooked on this series now and I’m aching for more information.

I need more!

An amazing series, please, please continue! I can’t wait to see which way you’re going with this!

did he died

I’d love to read more of this.

It’s so structured and easily explained that it makes me feel like I’ve just been reminded of something I already knew. That’s the best kind of teaching, in my opinion.

Actually, I did already use a lot of these methods when I started writing, but I forgot along the way, and got fixated on rhymes and rhythms.

Anyway, thanks for rekindling my inspiration!

Much love,

Tom.